#SPPC2021: Call for abstracts for posters for the 'Symposium on Palaeontological Preparation and Conservation'

#SPPC2021 will be held online on Monday 6th September 2021.

This event will be held online as part of the virtual meeting of the SVPCA (Symposium on Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy). SPPC2021 will be a 'posters only' meeting, with no ‘platform presentation’ talks, but there will be an opportunity for informal Q&A sessions with authors of posters.

Timetable of deadlines (all times are in GMT/UTC):

- Deadline for submitting abstracts: Midnight on Saturday 31st July 2021.

- Deadline for decisions made for acceptance of proposed posters: Friday 6th August.

- Registration for attendees is now open. Registration will close at midnight on 31st August, or when we have reached our capacity, whichever is sooner.

- The deadline for submitting the completed poster: midnight on Tuesday 31st August 2021.

- Registration has now closed - registrants (and those on the waiting list) should shortly receive an e-mail containing further details.

- The event begins at 15:00 BST (UTC + 01:00) with an hour to explore the Gather space and chat to others. There will then be poster presentations of ten minutes for each presenter, including questions. There will then be another chance to view the posters and chat before we wind down the event at 18:30 BST

- The latest version of the programme is available here

Background to SPPC: The SPPC is intended as a forum in which professionals, amateurs and researchers alike, interested in all aspects of preparation, conservation, model-making and related subjects, can participate. The SPPC offers a unique opportunity to meet friends and colleagues and to discuss recent developments, ongoing research, and other, often museum related, projects. Although the SPPC generally precedes the SVPCA conference, contributions are not limited to the field of vertebrate palaeontology. SPPC Conferences have been run since 1992, either before or after the SVPCA, and many participants attend both conferences.

Abstracts of previous talks and posters can be found here: https://www.geocurator.org/events/102-sppc/previous-years-of-sppc/520-sppc-previous-years

Have you considered joining GCG?

Have you considered joining GCG?

If you work with geological specimens, or are just interested in their care and use, then GCG membership is for you! You can find more details on this website!

- Membership - and sign up online

- If you have enjoyed SPPC, but don't want to join GCG, then you can donate (any amount, even the cost of a cup of coffee!) at https://www.geocurator.org/donate/ - Thanks!

#SPPC2021: Poster abstracts

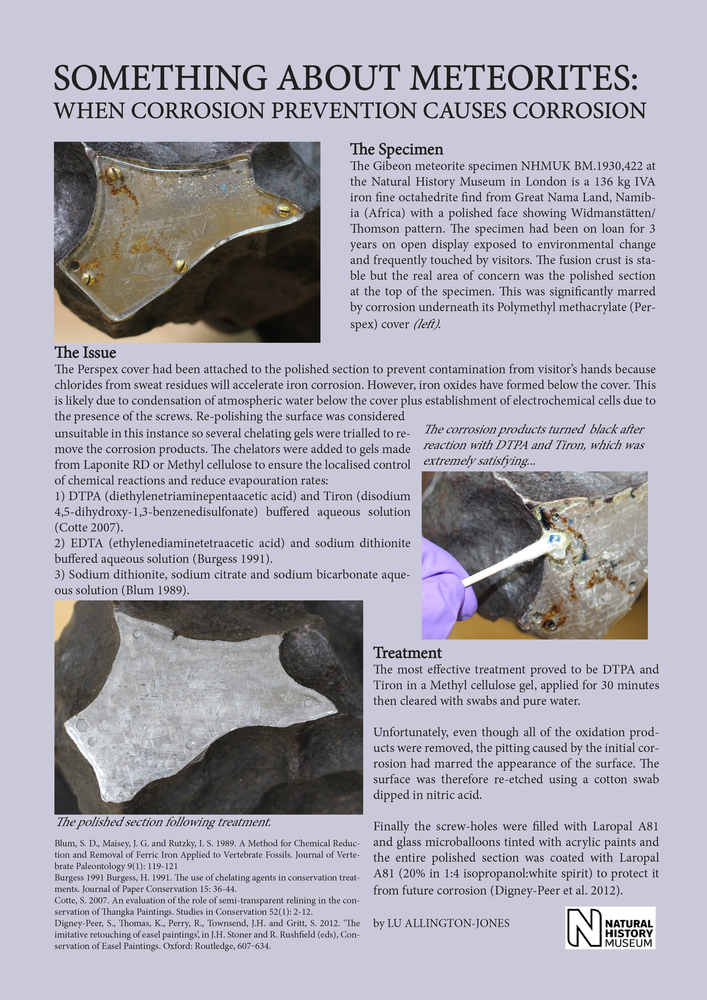

| Poster 1: Something About Meteorites: When Corrosion Prevention Causes Corrosion |

*

The Conservation Centre, Core Research Laboratories, The Natural History Museum, London, UK

Abstract: The Gibeon meteorite specimen NHMUK BM.1930,422at the Natural History Museum in London is a 136 kg IVA iron fine octahedrite find from Great Nama Land, Namibia (Africa) with a polished face showing Widmanstätten/Thomson pattern. The specimen had been on loan for 3 years on open display exposed to environmental change and frequently touched by visitors. The fusion crust is stable but the real area of concern was the polished section at the top of the specimen. This was significantly marred by corrosion underneath its Polymethyl methacrylate (Perspex) cover. The Perspex cover had been attached to the polished section to prevent contamination from visitor’s hands because chlorides from sweat residues will accelerate iron corrosion.However, iron oxides have formed below the cover. This is likely due to condensation of atmospheric water below the cover plus establishment of electrochemical cells due to the presence of the screws. Re-polishing the surface was considered unsuitable in this instance so several chelating gels (usually used in art conservation) were trialled to remove the corrosion products. The most effective treatment proved to be DTPA and Tiron in a Methyl cellulose gel. The surface was then re-etched with nitric acid and coated with Laropal A81.

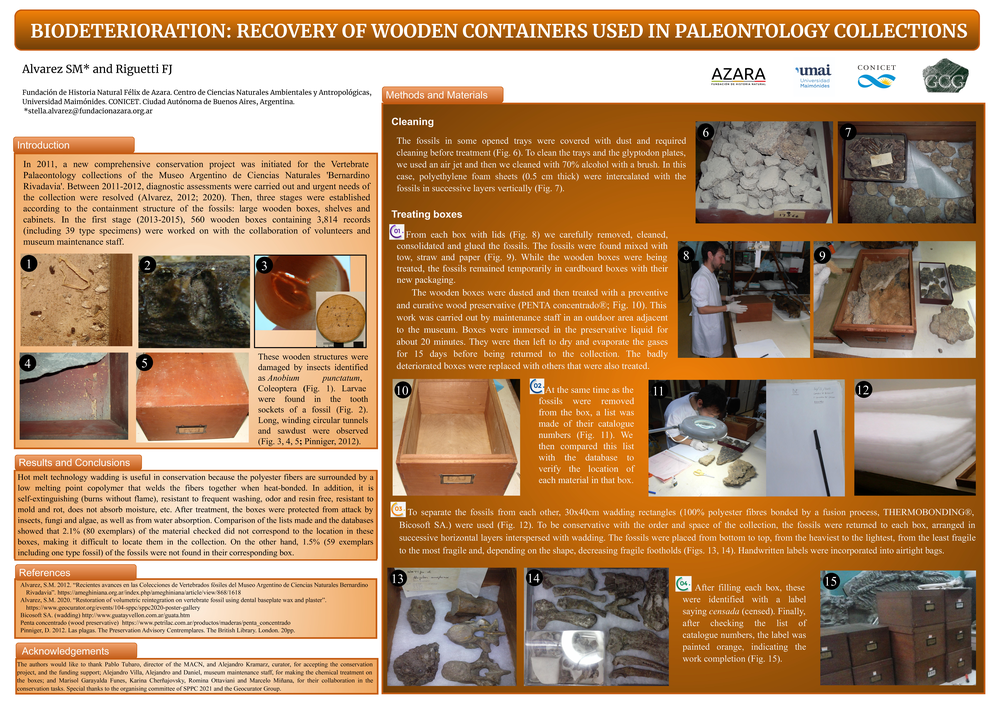

| Poster 2: Biodeterioration: Recovery of Wooden Containers Used in Paleontology Collections. |

Alvarez S.M.*1 and Riguetti F.J.1

Alvarez S.M.*1 and Riguetti F.J.1

*

1 Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara. Centro de Ciencias Naturales Ambientales y Antropológicas, Universidad Maimónides. CONICET. Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Abstract: In 2011, a new integral conservation project of the Vertebrate Palaeontology collections of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales 'Bernardino Rivadavia' began. Between 2011-2012, diagnostic evaluations were carried out and the urgent needs of the collection were resolved. Three stages were then established according to the containment structure of the fossils: large wooden boxes, shelves and cabinets. These structures were damaged by insects identified as Anobium punctatum, Coleoptera. Long, winding circular tunnels and sawdust were observed in the affected areas. In the first stage (2013-2015) we worked on 560 wooden boxes containing 3,814 records (including 39 type specimens) with the collaboration of volunteers and museum maintenance staff. In each box we were carefully removing, cleaning, consolidating and gluing the fossils; listing the catalogue numbers of the fossils; and comparing this list with the database to verify the location of the material in that box. Handwritten labels were incorporated into airtight bags. The old separation of the fossils with tow and straw was replaced by wadding (100% polyester fibres bonded together by a melt bonding process) or polyethylene foam. The boxes were treated with a preventive and curative wood preservative to avoid deterioration caused by biological agents.

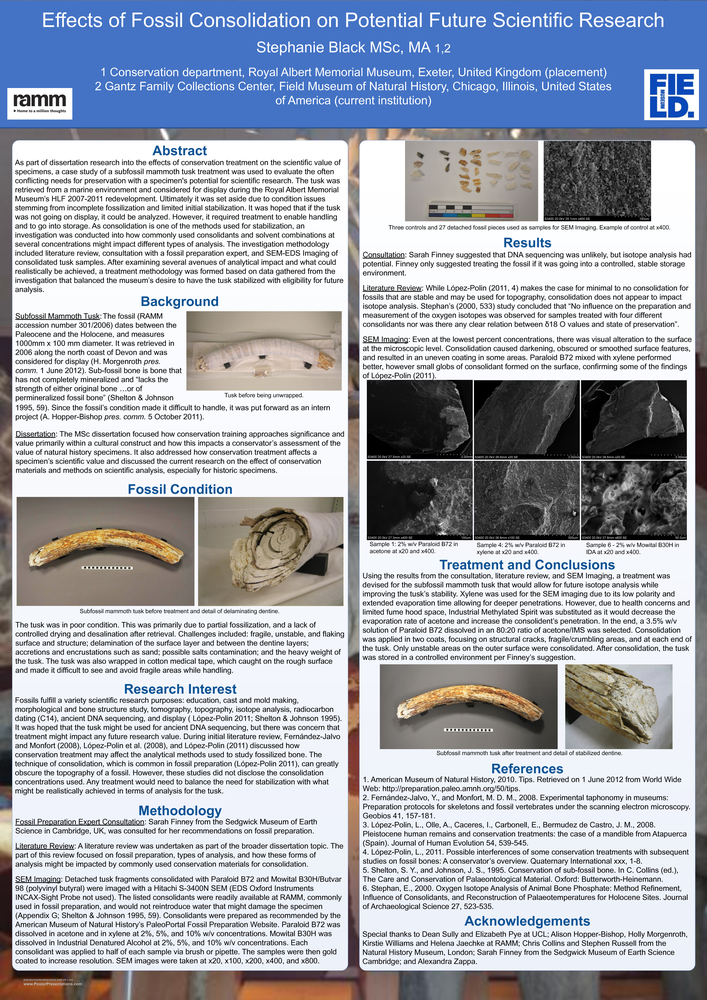

| Poster 3: The Effects of Fossil Consolidation on Potential Scientific Research |

*

1 Conservation department, Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, United Kingdom (previously)

2 Gantz Family Collections Center, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America (currently)

Abstract: As part of broader dissertation research into the effects of conservation on the scientific value of specimens, a case study of a subfossil mammoth tusk treatment was used to evaluate the often conflicting needs for preservation with a specimen's potential for scientific research. The tusk was retrieved from a marine environment in 2006 and considered for display during the Royal Albert Memorial Museum's HLF 2007-2011 redevelopment. Ultimately it was set aside due to condition issues stemming from incomplete fossilization and limited initial stabilization. It was hoped that if the tusk was not going on display, it could be analyzed. However, it required treatment to enable handling and to go into storage. As consolidation is one of the methods used for stabilization, an investigation was conducted into how commonly used consolidants and solvent combinations at several concentrations might impact different types of analysis. The investigation methodology included literature review, consultation with a fossil preparation expert, and SEM-EDS imaging of consolidated tusk samples. After examining several avenues of analytical impact and what could realistically be achieved, a treatment methodology was formed based on data gathered from the investigation that balanced the museum's desire to have the tusk stabilized and eligible for future analysis.

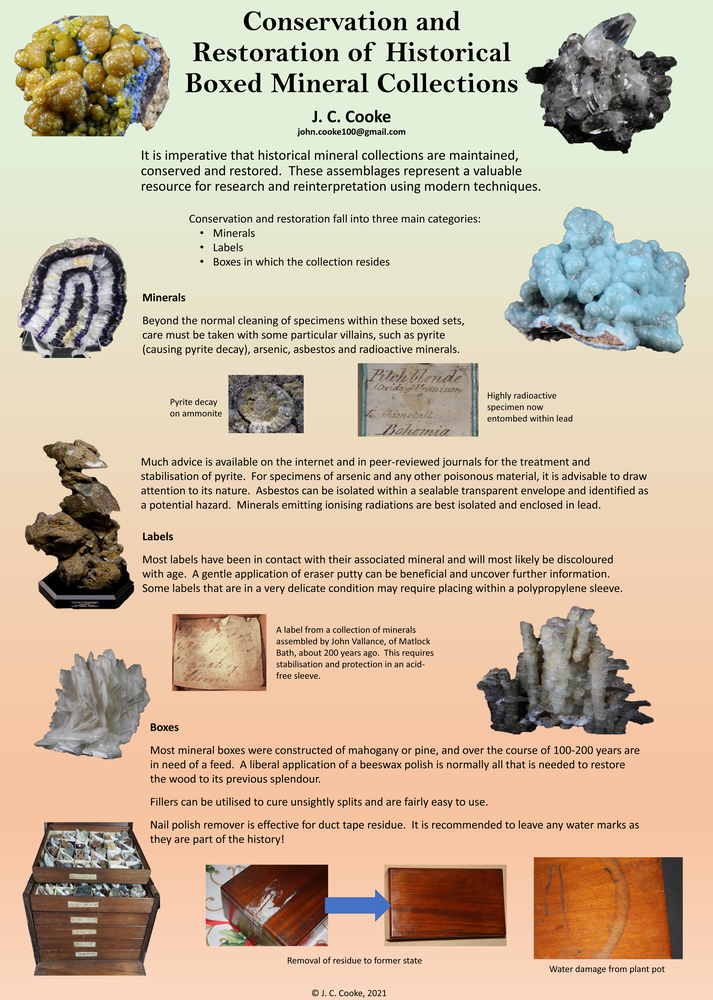

| Poster 4: Conservation and Restoration of Historical Boxed Mineral Collections |

*

Abstract: Historical mineral collections appealed to the contemporary as they do today, for example those aimed at the impulse buyer and the tourist. Other collections of a more scientific nature may have been attractive to the nobility and gentry to exhibit their interest in the emerging natural sciences. Higher quality collections were available to demonstrate regional geology and mineralogy. There were many suppliers that could satisfy this market as this was a useful adjunct (and income stream) to their established business. Such notable vendors would include John Mawe, White Watson, James Tennant, Bryce Wright and Gregory Bottley.

The many surviving antique collections represent the minerals that were available at any particular decade and are a snapshot of contemporary knowledge, mining techniques, ore extraction and the importance of ore constituents.

These are not stuffy old collections but repositories of knowledge and are available for reinterpretation using current investigative techniques.

It is of paramount importance that these valuable collections are maintained, conserved and restored. The poster session will give examples of mineral preservation and the need to apply care using our current knowledge of pyrite decay, asbestos (and related minerals) and ionising radiations. Conservation also extends to the fragile labels and to the boxes in which they were presented.

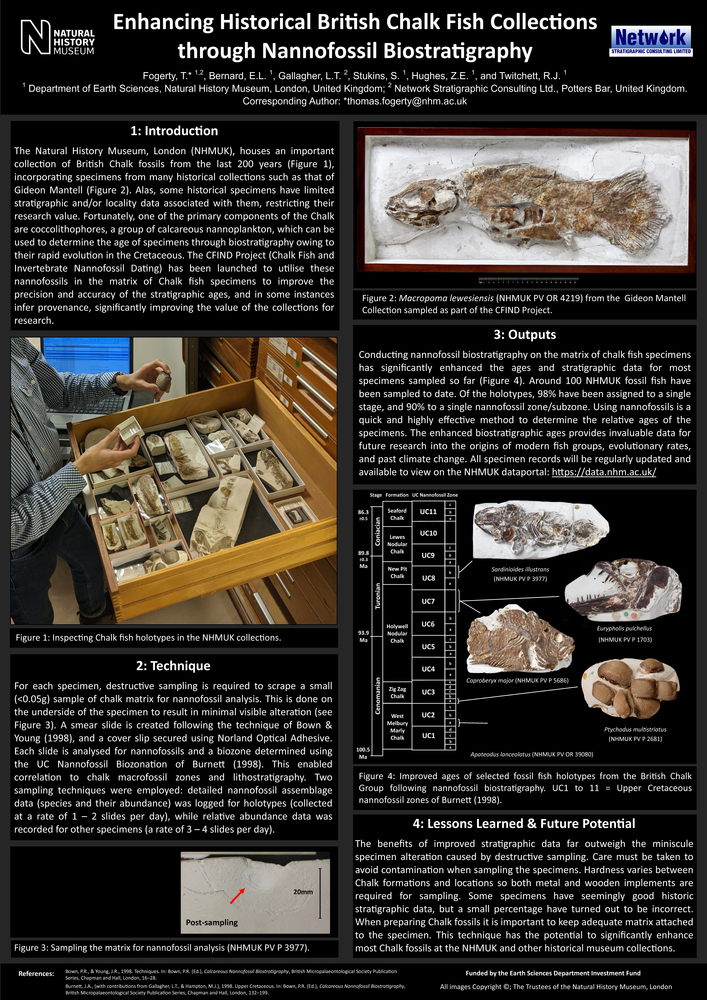

| Poster 5: Enhancing Historical British Chalk Fish Collections through Nannofossil Biostratigraphy |

Fogerty, T.* 1,2, Bernard, E.L. 1, Gallagher, L.T. 2, Stukins, S. 1, Hughes, Z.E. 1, and Twitchett, R.J. 1

Fogerty, T.* 1,2, Bernard, E.L. 1, Gallagher, L.T. 2, Stukins, S. 1, Hughes, Z.E. 1, and Twitchett, R.J. 1

*

1 Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom; 2 Network Stratigraphic Consulting Ltd., Potters Bar, United Kingdom.

Abstract: Calcareous nannofossils are a primary component of the British Chalk and owing to their abundance and high rate of evolution are a valuable tool for biostratigraphy, provenance analysis, and palaeoenvironmental interpretation. The Natural History Museum, London (NHMUK), houses an important collection of British Chalk fossils from the last 200 years, but some historical specimens can have limited stratigraphic and/or locality data associated with them, which restricts their research value. To address this, nannofossil biostratigraphy is being undertaken on Chalk fish specimens with the intent to improve the precision and accuracy of the stratigraphic ages, and in some instances infer provenance. This technique involves removing >0.05g of matrix from the specimen which is analysed for calcareous nannofossils. Using the latest biostratigraphic framework, a nannofossil zone or subzone is assigned, indicating the relative age of the specimen. Two methods were applied: 1: collecting detailed nannofossil assemblage data for biostratigraphic analysis and palaeoenvironmental data; 2: quick biostratigraphic analysis to verify pre-existing macrofossil zone data. Around 100 NHMUK fossil fish specimens (including most holotypes) have been analysed hitherto, significantly enhancing the stratigraphic ages for most specimens, providing invaluable data for future research into the origins of modern fish groups, evolutionary rates, and climate change.

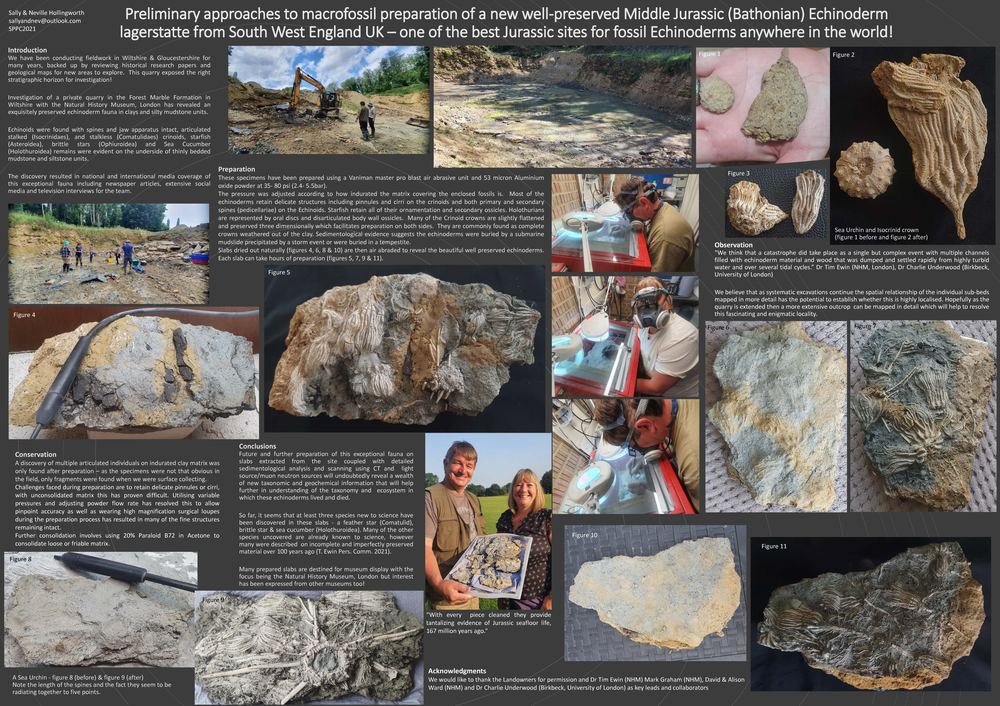

| Poster 6: “Jurassic Pompeii” Preparation of a Well-Preserved Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) Echinoderm Lagerstätte from South West England, UK. |

Hollingworth N.1 and Hollingworth S.1*

Hollingworth N.1 and Hollingworth S.1*

*

1 Science and Technology Facilities Council, Avtar Construction Ltd.

Abstract: Excavation of a private quarry in the Forest Marble Formation in Wiltshire with the Natural History Museum London has revealed an exquisitely preserved echinoderm fauna in clays and silty mudstone units. Echinoids are found with spines and jaw apparatus intact, fully articulated stalked (isocrinids) and free swimming crinoids (comatulids), starfish and holothurian remains are abundant on the underside of thinly bedded crinoidal mudstone and siltstone units and these have been prepared using a Vaniman pro blast airbrasive unit and 50 micron aluminium oxide powder at 35- 80 psi (2.4- 5.5bar). The pressure is adjusted according to how indurated the matrix is covering the enclosed fossils. Most of the echinoderms retain delicate structures including pinnules and cirri on the crinoids and both primary and secondary spines (pedicellarae) on the echinoids. Starfish retain all of their ornamentation. Holothurians are represented by oral discs. Many of the crinoid crowns are uncrushed and preserved three dimensionally which facilitates preparation on both sides, they are commonly found loose in clay and soft siltstone. Sedimentological evidence suggests the echinoderms were buried by a submarine mudslide precipitated by a storm event or were buried in a tempestite.

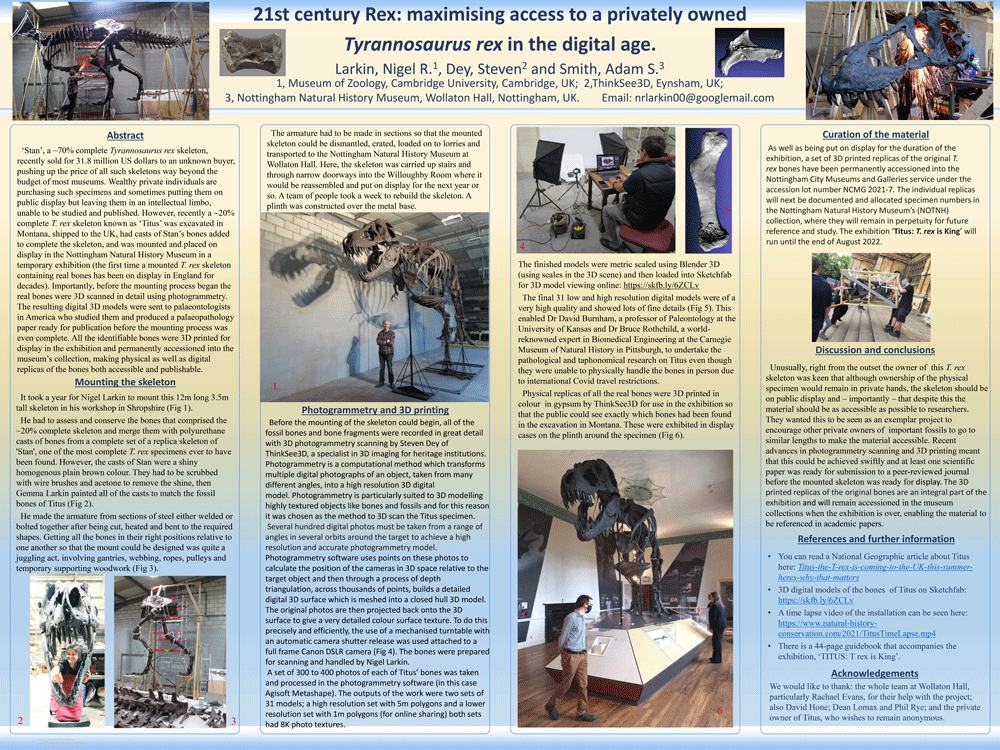

| Poster 7: 21st century Rex: Maximising Access to a Privately Owned Tyrannosaurus rex in the Digital Age. |

Larkin, N.R. *1, Dey, S.2 and Smith, A.S.3

Larkin, N.R. *1, Dey, S.2 and Smith, A.S.3

*

1 Museum of Zoology, Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK; 2 ThinkSee3D, Eynsham, UK; 3 Nottingham Natural History Museum, Wollaton Hall, Nottingham, UK.

Abstract: ‘Stan’, a ~70% complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton, recently sold for 31.8 million US dollars to an unknown buyer, pushing up the price of all such skeletons way beyond the budget of most museums. Wealthy private individuals are purchasing such specimens and sometimes putting them on public display but leaving them in an intellectual limbo, unable to be studied and published. However, recently a ~20% complete T. rex skeleton known as ‘Titus’ was excavated in Montana, shipped to the UK, had casts of Stan’s bones added to complete the skeleton, and was mounted and placed on display in the Nottingham Natural History Museum in a temporary exhibition (the first time a mounted T. rex skeleton containing real bones has been on display in England for decades). Importantly, before the mounting process began the real bones were 3D scanned in detail using photogrammetry. The resulting digital 3D models were sent to palaeontologists in America who studied them and produced a palaeopathology paper ready for publication before the mounting process was even complete. All the identifiable bones were 3D printed for display in the exhibition and permanently accessioned into the museum’s collection, making physical as well as digital replicas both accessible and publishable.

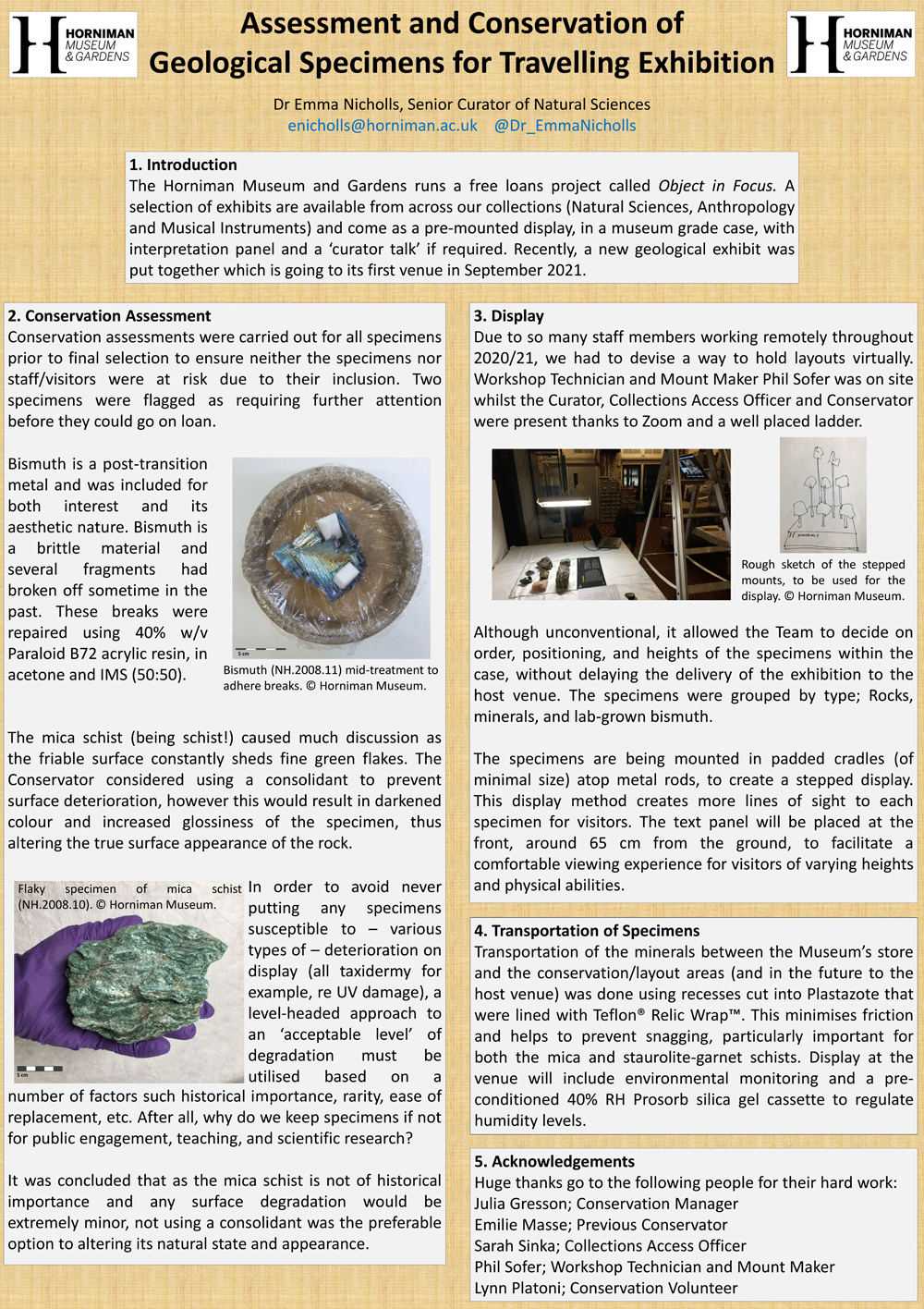

| Poster 8: Assessment and Conservation of Geological Specimens for Travelling Exhibition |

*

The Horniman Museum and Gardens, 100 London Road, Forest Hill, London, SE23 3PQ

Abstract:

The Object in Focus project comprises a selection of exhibits loaned to venues free of charge. The specimens come as a pre-mounted display, in a museum grade case with interpretation and a ‘curator talk’ if required. Recently, three rocks (mica schist, staurolite-garnet schist and granodiorite), three minerals (fluorite, rose quartz and chalcopyrite) and a bismuth specimen were chosen to be incorporated into the programme.

Conservation assessments were carried out, in which two specimens were flagged as requiring further attention before they could go on loan. The bismuth specimen is quite brittle and several fragments had broken off sometime in the past. These breaks were repaired using 40% w/v Paraloid B72 acrylic resin, in acetone and IMS (50:50).

The second was the mica schist as the friable surface left fine green flakes wherever it had been laid. Conservation considered using a consolidant to prevent surface deterioration, however this would result in darkened colour and increased glossiness, altering the surface appearance of the rock. The specimen is not of historical importance, so it was decided minor surface degradation was the preferable option.

Transportation of the minerals was done using recesses cut into Plastazote, lined with Teflon® Relic Wrap™, to minimise friction and prevent snagging. Display at the venue includes environmental monitoring and a pre-conditioned 40% RH Prosorb silica gel cassette within the case to regulate relative humidity.

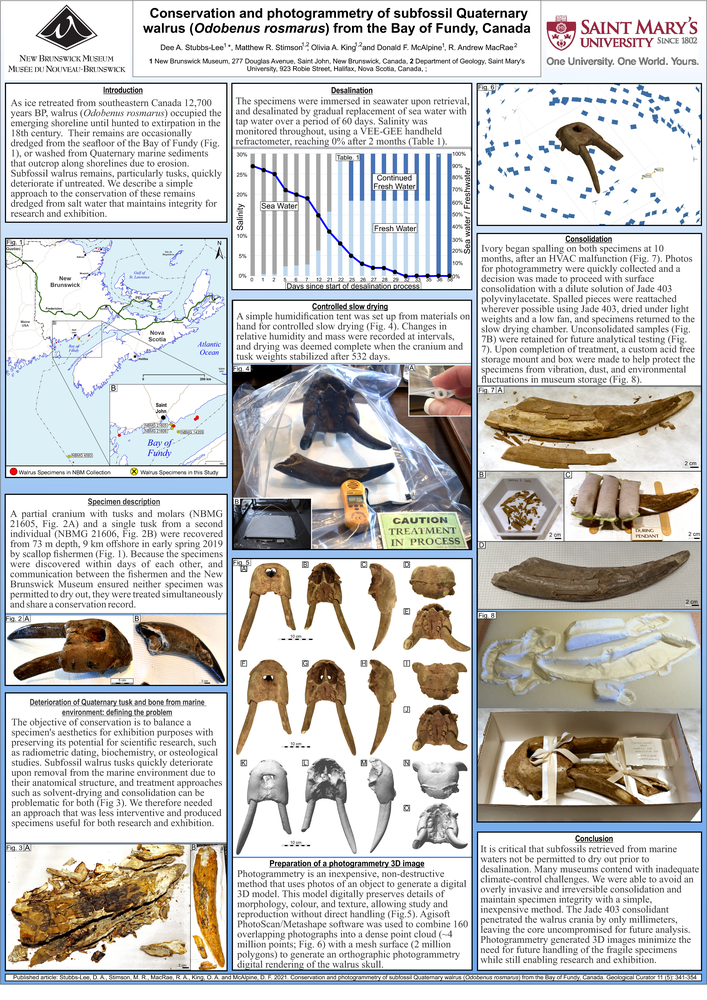

| Poster 9: Conservation and Photogrammetry of Subfossil Quaternary Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) from the Bay of Fundy, Canada |

Stubbs-Lee, D. A.1*, Stimson, M. R. 2,3, MacRae, R. A. 3, King, O. A.2,3 and McAlpine, D. F.4

Stubbs-Lee, D. A.1*, Stimson, M. R. 2,3, MacRae, R. A. 3, King, O. A.2,3 and McAlpine, D. F.4

*

1 Conservation Section, Department of Museum Services, New Brunswick Museum, 277 Douglas Avenue, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada, E2K 1E5; 2 Steinhammer Laboratory of Palaeontology, Geology and Paleontology Section, Department of Natural History, New Brunswick Museum, 277 Douglas Avenue, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada E2K 1E5; 3 Department of Geology, Saint Mary’s University, 923 Robie Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, B3H 3C3; 4 Zoology Section, Department of Natural History, New Brunswick Museum, 277 Douglas Avenue, Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada E2K 1E5

Abstract: We describe a simple, inexpensive approach to the conservation and preservation of the subfossil cranium and tusks of two Quaternary (c. 2,900–12,800 years BP) walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) specimens dredged from salt water. Mineral salt deposits within subfossil bone and tusk retrieved from marine environments will cause spalling and shattering over time, so desalination before drying is critical. Our hope was that with desalination, followed by a controlled slow drying process, we could avoid consolidating the specimens. Some limited spalling did, however, occur on the tusks during the slow drying process and was addressed by surface consolidation with dilute polyvinylacetate. A 3D digital image produced through photogrammetry permitted us to minimize the necessity of future handling and conservation treatment and to preserve details of overall morphology and meristics useful for both research and public exhibition. The use of two complimentary methods allowed us to preserve the evidence inherent in our two specimens for long term study. One method involved physical conservation of the actual specimens, while the other involved digital capture of the external features.

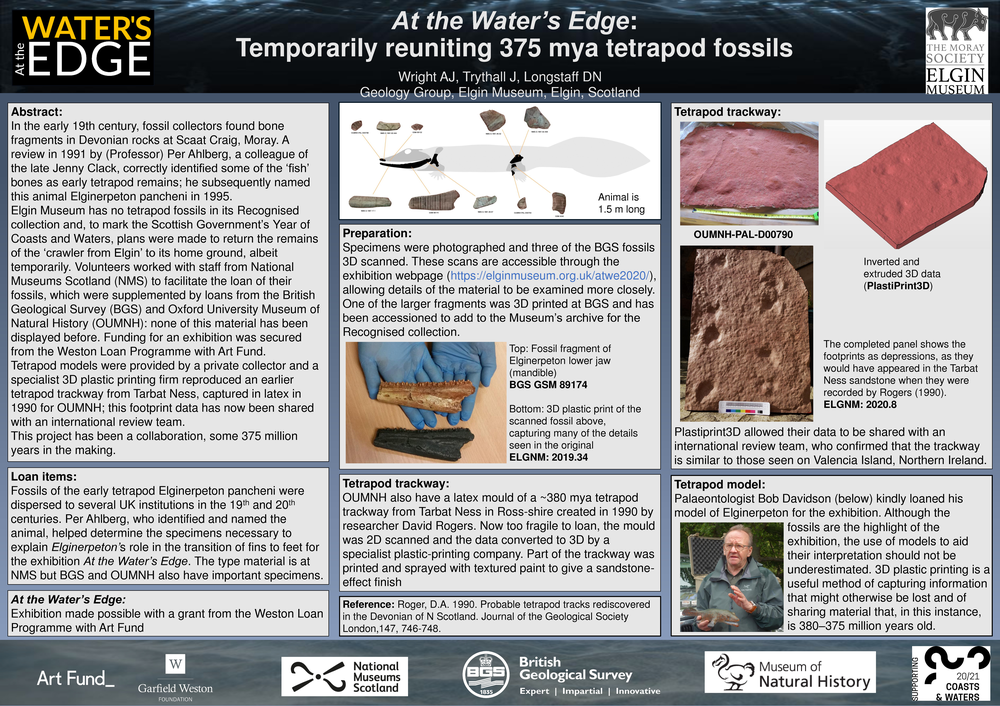

| Poster 10: At the Water’s Edge: Temporarily reuniting 375 mya tetrapod fossils |

Wright A.J.*1, Trythall J.1 and Longstaff D.N.1

Wright A.J.*1, Trythall J.1 and Longstaff D.N.1

*

1 Geology Group, Elgin Museum, Elgin, Scotland

Abstract: In the early 19th century, fossil collectors found bone fragments in Devonian rocks at Scaat Craig, Moray. A review in 1991 by (Professor) Per Ahlberg, a colleague of the late Jenny Clack, correctly identified some of the ‘fish’ bones as early tetrapod remains; he subsequently named this animal Elginerpeton pancheni in 1995.

Elgin Museum has no tetrapod fossils in its Recognised collection and to mark the Scottish Government’s Year of Coasts and Waters, plans were made to return the remains of the ‘crawler from Elgin’ to its home ground, albeit temporarily. Volunteers worked with staff from National Museums Scotland to facilitate the loan of their fossils, which were supplemented by loans from the British Geological Survey and Oxford University Museum of Natural History. None of this material has been put on display before. Funding for an exhibition was secured from the Weston Loan Programme with Art Fund.

Tetrapod models were provided by a private collector and a specialist 3d plastic-printing firm reproduced an earlier tetrapod trackway from Tarbat Ness, captured in latex in 1990 for OUMNH; this footprint data has now been shared with an international review team.

This project has been a collaboration some 375 million years in the making.